WWW.ILoveLBNY.Com

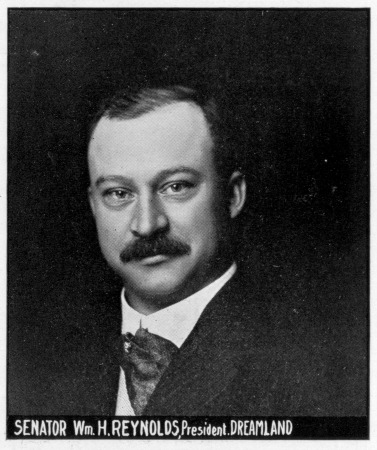

William H. Reynolds

LONG BEACH, NEW YORK

Photo Directories

Here is an item we found by accident from The Browstoner, a website about Brooklyn.

William H. Reynolds

Imagine, if you would, as Rod Serling used to say, a young man whose father is a builder. Dad does well, but the son has the real touch for the business of building houses. He helps his father, and ends up taking over the business, raising it to heights Dad never dreamed. He’s so good, while still in his 20’s; he hires his father to work for him. Eventually, he gets a bit bored with just building houses, so he starts to dabble in buying theatres, amusement parks and the like. He even goes so far as to develop entire neighborhoods, because this son of a builder thinks BIG. Along the way, he has a few setbacks, a lawsuit and a near bankruptcy. But in the end, he emerges triumphant, and sails off in his yacht. Am I talking about Donald Trump? Nah, the Donald was a lightweight compared to William H. Reynolds, one of the biggest developers, and newsworthy men of his day Brooklyn developer extraordinaire, New York State Senator, amusement park and theatre owner, mayor of Long Branch, Long Island, indicted and convicted swindler, athlete, yachtsman, and bon vivant.

William H. Reynolds was born in Brooklyn in 1867, the son of William Reynolds, a successful local builder, and his wife Margaret. He attended PS 35, on MacDonough Street in Bedford, Brooklyn, and went on to Central Grammar School. He was accepted into Harvard, but he never went. He did study law for two years at the University of New York, but he did not graduate. As a lad, he spent his after- school hours cleaning up after the workmen in his father’s business. He soon figured out that his father didn’t pay his bills on time; he got to them when he got to them. He went to his father’s accounts and made a deal with them: if he could get the elder Reynolds to pay his bills by the first of the month, then there would be a 2% discount off each bill. The vendors were glad to have their bills paid on time, and the father was glad to have someone else taking care of the bills. William paid the bills, and pocketed the 2%.

At the age of 18, he opened a real estate broker’s office on the corner of Reid and Lafayette, and by the end of the first year, had a profit of over $40,000. ($921,000 in today’s money) Starting in 1885, the Brooklyn Eagle is flooded with ads for houses in the 25th ward, now the proposed Bedford Corners Historic District section of Bed Stuy, near Fulton, Nostrand and Marcy. He started to buy land and develop property, first in Bedford. He was living at 273 Hancock Street, between Marcy and Tompkins, at this point, and his office was now on Fulton and Washington. He was so successful that he offered his father a job, which he accepted. He built fast and inexpensively, and sold reasonably, his houses going for $15,000 to $20,000, everything so fast moving, that by the time he was done in Bedford, he had amassed $500,000 in profit ($11.5 million today).

Prospect Park

William was only just beginning. In the early 1890’s he turned his attention to a swath of neglected land bordering Prospect Park. It had been tied up in litigation for several years, because the city of Brooklyn had bought the land through eminent domain, in order to build Prospect Park, but as time passed and different planners came on board the project, specifically Olmstead and Vaux, the site of the park moved west, and this land was no longer needed. The City wanted to unload the land, but was unable to do so at a profit, and had to have a fire sale. Reynolds bought up the neighborhood, specifically what are now Sterling Place and Underhill Avenue, at least 80 lots in all. He then proceeded to build row houses on all of these blocks. On some documents he is listed as the architect of record, on others, as the developer. Dahlander and Hedman, were his architects in some of his developments here, as well. The houses were built quickly, and are among the most attractive buildings in the entire neighborhood.

NYS Senator

At the same time, William H. Reynolds felt the call to politics. While his Prospect Heights buildings were going up, he campaigned for, and won, the seat for the Third District, and in 1893, at the age of 24, became the youngest senator in the NY State Senate. He was hailed as a good Republican, and an independent free thinker, who was not beholding to any faction or political club. By 1895, he had been appointed as chairman of the Republican campaign committee, but bowed out of politics that same year. Meanwhile, ads for his houses on Sterling Place were appearing in the Eagle, and in the next couple of years he finished and and sold all of his houses on these blocks, and was renting apartments in 1895 in his new apartment buildings on Vanderbilt, near the park. By 1897, the houses on Park Place had been built, and those, too, were selling at an extremely fast pace.

Things were going really well for Reynolds. He was a respected and popular senator. He was a very successful developer and builder. But he must have been getting a bit bored. In 1894, he bought a large parcel of land on Fulton Street, near DeKalb, home to Sherlock’s Abbey Theatre, where he proposed to build the finest, and with one or two exceptions, the largest theater in the country. It will be by all odds the largest and most comfortable in Brooklyn and will compare favorably with the Metropolitan Opera house of New York City. The theatre was called the Montauk, and was designed by JB McElfatrick and Son, of Manhattan. It opened with great success and fanfare a little over a year later. In 1895 he rebuilt the Bennett Casino, on East New York and Alabama Avenues for impresario Otto Huber, called one of the best concert halls in the country. He used the same architects as on the Montauk. He also used McElfatric and Son when he built his dream home on the corner of Eastern Parkway and Underhill Avenue, in 1895. The huge, four story mansion was featured in the Eagle, complete with drawings and a floor plan of the parlour floor. The house featured the usual expansive and impressive public and rooms, but the highlight for Reynolds himself was probably the ground floor, which featured a large billiard room and an expansive gymnasium, complete with showers. In addition to everything else, William Reynolds was also an accomplished athlete, the winner of several boxing awards in his youth, a boxing trainer, and a member of the Aetna Athletic Club.

William H. Reynolds was a turn of the century mover and shaker in Brooklyn. One hundred years later, he is hardly known, but in his day, this Brooklyn native was an influential builder, real estate developer, politician, and entrepreneur. The last Walkabout chronicled his early days as a young and successful real estate broker and developer in Bedford Stuyvesant and Prospect Heights. He was responsible for building much of Prospect Heights, also while serving in the New York State Senate as its youngest member. He didn’t stay in the Senate very long, only one term, but that job gave him political connections, name recognition, and the right to call himself Senator for life, always a handy title to impress potential business partners and investors. By 1898, Reynolds had more or less finished up his work in Prospect Heights. His row houses, centered primarily on long stretches of Park and Sterling Places, were almost all sold, and he had built successful apartment buildings on Vanderbilt and Underhill, as well as his own palatial home on the corner of Underhill and Eastern Parkway. He needed a new challenge. The suburban reaches of Brooklyn were still out there, especially in the more southern areas of Brooklyn, so he bought up a large parcel of undeveloped land, and carved 4,000 lots from it, sold lots to investors, and started building on them himself. He called his new neighborhood Borough Park.

Borough Park

By 1899, Borough Park was in full swing. The Brooklyn Eagle had daily ads advertising Reynolds’ newly built homes, most of which were large, detached suburban looking homes. He built himself a new house there, as well, on 49th St and 15th Avenue, where his wife organized community events. Not content to just develop, Reynolds was very instrumental in shaping his new community, as well. In 1899, he fought another builder’s desire to build four story tenement buildings with ground floor storefronts, specifically a butcher and a grocery. The injunction he won prevented stores from being built in Borough Park, calling them detrimental to the interests of the neighborhood. One of his biggest public relations stunts, used to sell homes and lots in Borough Park, was to bet on the presidential election of 1900. The candidates were William Jennings Bryan, Democrat, and William McKinley, Republican. Reynolds, a life-long Republican, made a wager, as advertised in the Eagle, that McKinley would win. If he didn’t, any buyer of one of his properties in Borough Park, who chose to take up the wager, would receive his property free and clear. The property had to be purchased because of the wager, and before the election. He advertised this wager frequently in the Eagle, daring anyone to come forward, and perhaps receive a free house. It is not known how many took him up on the offer, but they all lost. McKinley won the presidency, only to be assassinated a year later. Reynolds sold a lot of houses.

With Borough Park developing nicely, Reynolds started looking around for more projects. He developed in Bensonhurst and in Westminster Heights. He already owned a couple of theaters, the most important being the Montague, in Downtown Brooklyn, and he had another Montague Theater on Pitkin Avenue in Brownsville. He loved musical extravaganzas, and in the late 1890’s added the Casino Theater in Manhattan to his list of theaters. But even the largest theater can only hold so many people. Why not build something that can entertain thousands at one time, and have the most impressive show of all? What could be better than an amusement park?

Coney Island

On May 14, 1904, William H. Reynolds opened Dreamland, his $3.5 million dollar amusement park at Coney Island. Thousands of workers worked day and night to complete the project in less than six months, making it the largest entertainment project of that magnitude to be constructed in so short a time. The most spectacular feature of Dreamland was it enormous tower, which stood in the center of the park, in 1904, one of the tallest structures in the United States. The tower was 375 feet tall, studded with 100,000 electric lights, and it dominated the entire Coney Island landscape. Elevators took people to the top, where they could see for miles around, including all of the Coney Island attractions. The best approach to the park was by steamboat, where the impressiveness of the Dreamland tower simply took people’s breath away.

Dreamland had plenty of other attractions, as well. The Dreamland Ballroom was on the pier, the largest in the world at 25,000 square feet, and the most popular ballroom on Coney Island. It was connected to a restaurant, almost as large, which served the finest cuisine. Other attractions included Shoot the Chutes, a flat bottomed boat ride, Leap Frog Railway, a roller coaster type ride with trains that crossed each other at the same time on separate tracks, one above, one below, and Coasting through Switzerland, which featured cars on tracks that passed through realistic depictions of Swiss villages and the Alps. The ride would pass the Matterhorn and Mount Blanc and quaint Alpine villages. Electric lights would recreate sunrises and sunsets, and fans blew across dry ice to deliver cooling Alpine breezes, making this ride a favorite in the hot summer. Another popular attraction was Fighting the Flames a realistic reenactment of fire and rescue on a city block. The show opened with a hotel on fire and trapped people screaming. The fire alarm sounds and firemen are shown waking up and sliding down the pole in the firehouse and racing to the fire. As the fire progresses up the building, the people are forced to the roof, where they jump into nets and are rescued while the fire is put out. All in time for the next show.

Dreamland also featured a wild animal act, and saw the display of the first human baby incubators. A Paris pediatrician named Dr. Martin Arthur Couney brought his incubators from Paris and Berlin, where they were not accepted by the medical community, eventually finding his way, first to Coney Island’s Luna Park and then nearby to Dreamland, in 1904. His incubator building looked like an old German farmhouse, and as the years went by, he saved more and more babies through this technology, so that by 1941, at the end of his career, his Coney Island incubator clinic had seen more than 8,000 babies, of which he was able to save over 6,500. In addition, Reynolds had his new manager of Dreamland, Samuel Gumputz, travel to World Fairs and other exhibitions to bring back the best to Coney Island. In 1904, he purchased the attraction called Creation from the St. Louis Worlds Fair for the 1905 season. It was not only an attraction, it became the entrance to Dreamland, the grandest entrance ever.

Creation was the largest illusion ever constructed for its time. It was the Genesis story of creation, with a boat ride around the firmament of heaven, with The Great Dome, where the world was created, including the land and the sea, ending with The Garden of Eden, where man was created. The ride was immensely popular, leading to the building of more Biblical attractions, including The End of the World, where Gabriel blew his trumpet, causing the world to quake. Another part of this attraction was called The Hell Gate, a realistic depiction of an ocean whirlpool. Passengers sat in boats which began to swirl around a 50′ whirlpool, which carried the boats down to the center of the maelstrom. At the last minute the slope would dip, and allow the boat to slip into an underground canal complete with rocks, reefs and shipwrecks, all on the bottom of the ocean floor. It must have been quite the ride. See the Flickr page for more photographs. Unfortunately, Hell Gate turned out to be a prophetic and tragic name. On May 27, 1911, at 1:30 in the morning, some workers working on this ride started a fire that spread, and soon destroyed the entire Dreamland park. It was the largest fire in New York State history. William H. Reynolds’ Dreamland was no more.

From sweeping up wood chips in his father’s shop, to hiring his father for his successful real estate and building business, to neighborhood creation and Creation (the ride) itself, William H. Reynolds had the golden touch. He had a large hand in shaping late 19th and early 20th century Brooklyn, perhaps more so than anyone else to date. He also lived large and well. In addition to his accomplishments told here and here, he was also, at various points in his life, an oil promoter, a copper mining man, and a racetrack builder and operator. He built and operated the Jamaica Racetrack for over ten years. He also operated a water company and a trolley line. He was an active athlete, and he loved yachting. In 1899, Reynolds took advantage of his growing fortune, and bought himself another yacht. It was a 120′ schooner called the Florida. The sale was paid for with $16,000 of Borough Park land to the seller. He was a member of the Atlantic Yacht Club, and this was not his only yacht. He also had one called the Wanderer, which he bought from one of the members of the Gould clan. The sale made the papers, which also chronicled, a year later, the death of the yacht’s captain, who drowned when he slipped and fell from the rowboat ferrying him from the Wanderer to another vessel at 2 in the morning.

In 1906, Reynolds’ company awarded what was called the largest contracting job ever, to the M.C. Madsen company, to construct paved roads, sidewalks, and general improvements to his new project in the Jamaica section of Queens. He called this 300 acre tract Laurelton, and announced plans for 50 large suburban houses, a clubhouse, and a Long Island Railroad Station house for his new Laurelton stop. Over a million dollars was to go into the project.

Long Beach Begins

With Coney Island’s Dreamland a huge success, William Reynolds gaze turned to farther out in Long Island. In 1906, at the age of 39, Reynolds, in partnership with some very heavy hitters, the presidents and vice-presidents of some of Brooklyn and Nassau County’s biggest banks and trusts, formed the Long Beach Estates, for the purpose of heavily investing in the resort town of Long Beach, practically an island on the outer barrier of Long Island’s South Shore. The town had been a popular tourist and vacation town since the 1880’s and featured sandy beaches and large resort hotels. The largest was the Long Beach Hotel, billed as the largest hotel in the world, which burned to the ground on July 29th, 1907. 800 guests poured onto the beach, with 8 people injured by jumping out of windows, and one fatality. One of the guests was William Reynolds, who helped organize a fire brigade and rescue crews. He and his partners had just paid $1.5 million for the property only 2 months earlier. It was a total loss. However, they were now in possession of the entire oceanfront, and they proceeded to buy the rest of the island from the town of Hempstead. They planned to build a boardwalk, homes and hotels. In order to bring in more tourists and guests, Reynolds had a channel dug to widen the waterway to accommodate steamboats and seaplanes. Over 320 men, working in shifts twenty-four hours a day, dredged the waterway, creating a channel 1,100 feet wide, twelve feet deep and five miles long on the north side of the island. It was the largest dredging project of its time, surpassed only by the Panama Canal. This new waterway was named Reynolds Channel.

As a publicity stunt, which also had a practical application, Reynolds had a herd of elephants brought to the beach from Dreamland. The elephants helped move lumber used to build the bulkhead along the beach and the miles of boardwalk. The boardwalk was 50′ wide, flanked with electric lights on both sides, and the project cost $136,000 a mile. As all this was going on, streets, sewers, gas and electric conduits were laid, sidewalks were laid out, and trees planted. In 1914, the village of Long Beach Estates elected its first mayor. Not surprisingly, it was William H. Reynolds. He called Long Beach the Riviera of the East, and mandated that every building was built in what he called an eclectic Mediterranean style, with white stucco walls and red tile roofs. He also mandated that the homes could only be occupied by white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. It wasn’t until his company went bankrupt in 1918 that these restrictions were lifted. The new town was very popular with wealthy businessmen and entertainers, as well as day trippers. Reynolds built a theater called Castles by the Sea with the largest dance floor in the world for dancers Vernon and Irene Castle. Photographs and postcards from the first third of the century show large crowds of people enjoying the beach, the many hotels and amenities, and the sun and fun. (Long Beach later became known for the many entertainers who vacationed and entertained there, including Mae West, Zero Mostel, Humphrey Bogart, Cab Calloway, Rudolph Valentino, Clara Bow and James Cagney. Billy Crystal was born and raised there, and Long Beach was the setting for the Godfather).

But behind the hotels and their famous guests, all was not well in Long Beach. In 1922, Long Beach was designated a city by the state Legislature, and William Reynolds was elected again as the new city’s first mayor, a much large position than mayor of his smaller village. His Long Beach Estates company had gone bankrupt in 1918, owing more than $5 million dollars, but he remained a popular and influential figure. However, in 1924, he and his city treasurer, John Gracy, were indicted for grand larceny and graft. The indictments stated that they had stolen over $8,000 in Long Beach city funds to pay off contractors who had not done work they were contracted to complete for the city, and that Reynolds had known the work wasn’t done, but ordered Gracy to cut checks for these men anyway. Gracy was complicit because he also knew the work hadn’t been done, and had cut checks without the usual proof of completion, or even invoices and receipts. Larger sums of money were also in question, as well, in schemes involving bonds issued and traded against services rendered in construction of sewers and other construction projects. A jury found Reynolds guilty of graft, and he was sentenced to at least 10 years in prison. Local lore says that the clock in the city hall tower was stopped in protest. Almost a year later, in 1925, the judgment was overturned on appeal, and Reynolds was released. Almost the entire population of Long Beach was on hand to welcome him back, and the clock was turned back on. In 1927, Reynolds was again cleared of larceny charges, and all indictments were dismissed. He was already working on another project, the development of Lido Beach, east of Long Beach, spending $5 million to build a luxury hotel/club called the Lido Country Club, followed by the development of the Lookout Point Beach, in 1930.

Not content with properties in Long Island, Reynolds also owned land in Manhattan. His most well known parcel was the land he had leased from Cooper Union, on the corner of 42nd and Lexington. It had been his desire to build the world’s tallest building on that spot, and he had engaged architect William Van Alen to design an 808 foot skyscraper with an observation deck. The designs were drawn up, but Reynolds decided to sell the land lease and the designs to Walter P. Chrysler in 1928, for over $2 million. Chrysler adapted those plans, and went on to build the iconic Chrylser building in 1930. It is not known why Reynold’s abandoned his plans. His Reynolds Building would have made him a household name. On October 20th, 1931, William H. Reynolds died at his apartment at 200 West 57th Street, in Manhattan. The cause was heart disease, he had been ill for several months. He was only 63. His obituary in the Times was a long one, and chronicled his very full life, noting that he had been very generous to charities, especially the Elks club to which he belonged, and several hospitals on Long Island. The paper noted that at his death, he had been president of the Lido Realty Corporation, Long Beach On the Ocean, Inc, the Alert Associates, Inc, Blythedale Water Company, and the Raylex Corporation. He was also on the Board of Directors of the Long Island Safe Deposit Company, and had once been president of the Long Beach Railway Company. He left a summer home at the Lido Club, and his wife, Elise, and two daughters, two sisters, and a grandchild. His estate was estimated at over ten million dollars, half of which went to his wife, with his two daughters splitting the rest. William H. Reynolds did return to Brooklyn at the end, and remains here now. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. With all that he achieved, it’s a wonder he didn’t figure out how to own that too. It’s a nice plot of land.

.